Climate change: trees to the rescue

Bringing nature back into cities can help fight global warming

Original article from Urban GreenUP project.

Fighting climate change is the challenge of the century. The last UN Environment Emissions Gap Report warned that, in order to ensure global warming stays below 2°C, efforts should be tripled, and if we want to stay below 1.5°C, they should be increased around five times.

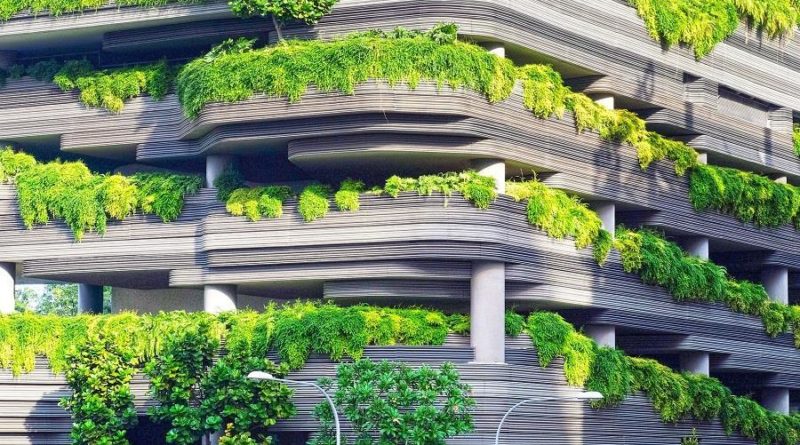

Researchers think one weapon to use is something that could actually make cities much more beautiful and pleasant: this weapon is nature itself. The so-called “nature-based solutions” (NBS), such as vertical gardens or green roofs, are being studied in many cities to tackle environmental and societal issues.

Urban areas occupy only 3 percent of the planet’s surface, but they are responsible for 75 percent of gas emissions. According to projections, by 2050, 6 billion people – or at least 70 percent of the global population – will be living in metropolitan centres, which might become a living hell, considering the impact climate change has on them: heat waves, periods of heavy rains that already have become more frequent and longer, drought, and other extreme weather patterns.

“Mitigation†refers to putting in place actions to limit the magnitude of climate change, while “adaptation†is about making cities liveable even once global warming will be at its worst. According to Italian architect Elena Farnè “trees are the only technology capable of both mitigation and adaptation. They are able to absorb, store and assimilate emissions, and therefore to combat climate change, mitigating on a global level. But trees also reduce temperatures in their areas, enabling adaptation locally.†How? Through evapotranspiration as “they release water vapour which is colder than air,†explains Farnè.

The architect took part in an Italian project called REBUS (REnovation of public Buildings and Urban Spaces), which studied the effects of climate change in cities and how to fight them through NBSs. The researchers found, for example, that rows of continuous and contiguous trees work better than an isolated tree: in terms of mitigation and adaptation, they act in a way that is greater than the sum of their parts, as if they were almost twice as many.

Another interesting aspect is that trees actually create urban breezes, which can be managed just by putting the right trees in the right places in the right order. And this wind also helps to lower the temperature in the city.

Of course, nature-based solutions are not only about trees. A number of technologies have been developed in the last years, such as environment-friendly pavements, green roofs or green walls which have been tested, for example, in Liverpool, UK, which is one of the “front-runner†cities of the EU project URBAN GreenUp. Or, in Sheffield, where you can see green roofs on bus stops. Across the border, France even introduced laws in 2015 requiring new buildings in commercial zones to incorporate vegetation or solar panels on their roofs.

What about the benefits of these layers of vegetation? They act as insulators during cold weather and have a cooling effect during hot weather, thus lowering energy use. They also help to absorb greenhouse gases and soak up excess water, thus reducing rain run-off.

Research requires investment and a lot of political will. And although the EU is pushing for NBS to be studied and implemented in a number of cities, there’s still a lot of work to do globally. Some countries, especially in the developing world, are more interested in growth and large-scale construction than in environmental protection. However, there are virtuous examples. Let’s take Turkey: Istanbul is turning more and more into a mass of concrete, while Izmir is developing an ambitious renaturing urbanisation programme, under the above-mentioned URBAN GreenUP.

Environmental engineer Kaan Emir, who works with municipalities in Turkey to get them involved in EU projects, thinks that it is necessary to educate people, starting with mayors. “It’s good to be part of this kind of project,†he says, “because the authorities are also interested in budgets, so if you find some funding they get more aware of the problem. And when they see, for example, what Izmir is doing, a sort of race starts among cities. We use this to provoke them: if that city can do this, why can’t you?”

By Selene Verri

29 January 2019